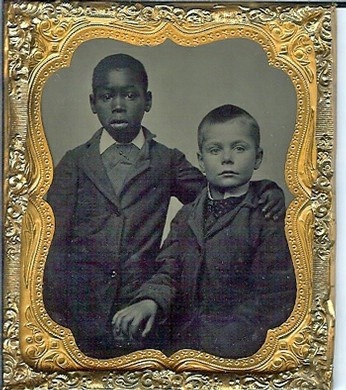

Black Boy and White Boy, 1880

Source: Vintage Photos

While researching for an African Diaspora family, I ran into special challenges that many beginners and novice ancestral story seekers may also face: l

The enslaver’s son and an enslaved man were born the same year and had the same name. The enslaver owned plantations in two different states — North Carolina and Louisiana.

Both of these situations can slow down research and make the puzzle pieces harder to fit together.

My “Check It Twice” Approach

When this happens, I do what I call my “St. Nick” and “Show Me State” review. Like Santa Claus I make a list and check it twice (sometimes more!). Like Missouri, the “Show Me State,” I make sure the documents prove the story before I connect the dots.

This means I don’t rely only on census records. I dig deeper into:

-

Newspapers (for sales, obituaries, or runaway notices),

-

Church records (baptisms, marriages, funerals),

-

Plantation diaries and letters,

-

Probate records (wills and estate inventories), and

-

Slave Schedules from 1850 and 1860 (which list only age and gender, not names).

These extra sources help me separate individuals who at first glance might look like the same person.

Why the Mix-Ups Happen

On large plantations, it was very common for children — both enslaved and free — to be born in the same year, and sometimes even given the same name. Wealthy enslavers often had more than one home or plantation. Many families in the Upper South (like North Carolina) also invested in property in the Deep South (like Louisiana), where cotton and sugar plantations brought bigger profits.

So, it’s no surprise when family trees overlap or records get tangled together.

What It Means for Family Researchers

Some online genealogy sites automatically merge people with the same name and birth year, even if they were two separate individuals. That’s why it’s up to us as researchers to slow down, double-check, and make sense of the data.

For African Diaspora families, this work often involves extra layers of investigation compared to white counterparts, because records for enslaved people were limited, scattered, or deliberately obscured.

What’s Next

In a follow-up blog, I’ll walk through the exact steps I used to tell apart the two men in this case — one the enslaver’s son, and the other an enslaved man — who happened to share both the same name and birth year.